The destiny of a raindrop falling near Trentham

A journey down the Loddon River

By Alison Pouliot

This is the fifth article in the series looking at the rivers that rise in the Wombat Forest. With a length of 392km, the Loddon is the Wombat's longest river.

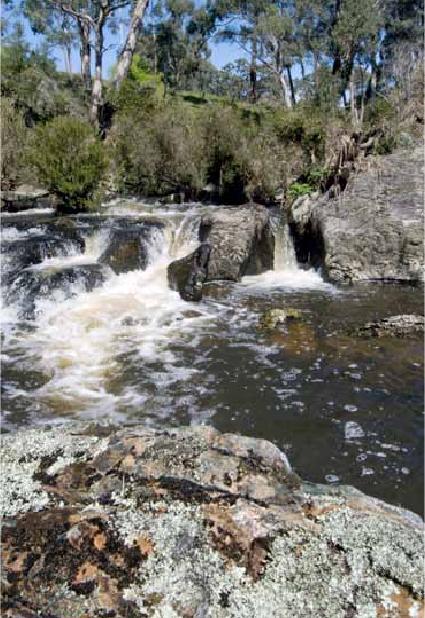

The Loddon River in high flow at Loddon Falls (Photo by Alison Pouliot)

It's raining. My favourite time to be in the Wombat. It's all damp earth and swirling cloud and intense forest scents. I'm near the source of the Loddon River, not far from Trentham, where some of the Wombat's most majestic trees stretch into the misty canopy. A single glistening water droplet catches my eye, momentarily shivers, then slips down a fern frond. This solitary water droplet then undergoes a journey across the soil to form part of the Loddon's headwaters.

The droplet soon departs the tall cool eucalypt forest and heads northward, tumbling over the basalt columns of Glenlyon Falls. It glides by platypus and native fish and further downstream traverses box-ironbark country, squeezing through the lichen-splattered boulders of Vaughan springs and onward past Guildford and Newstead. As the landscape dries out and trees become sparse, it may spend time in Cairn Curran or Laanecoorie Reservoirs, before continuing downstream to Bridgewater. Towards the end of its Loddon journey it flows into the Murray River near Swan Hill.

But during its course, a most bizarre thing might happen. It could be traded.

Gambling with water

Water Trading is simply the buying and selling of water access entitlements. It's not a new concept. South Australia first introduced water trading in the early 1980's. The scarcity and hence economic value of water has long been recognised in Australia. Water was being sold soon after European colonisation as settlers polluted their own local supplies and had to buy it from further upstream. Australian history is deeply embedded in a succession of struggles for water across every state and territory. But has it all gone too far? At some point water has ceased to belong to the rivers, to the catchments and to all the life it supports. Something is seriously odd when a government must buy or buy back water to allow it to flow down a river. Water has become tradable property, and if you're lucky enough to have a 'water access entitlement', you can sell your water allocation for a decent profit. But what are the real costs of applying market principles to water and has its commodification had any real benefit to the rivers?

Aquatic connections

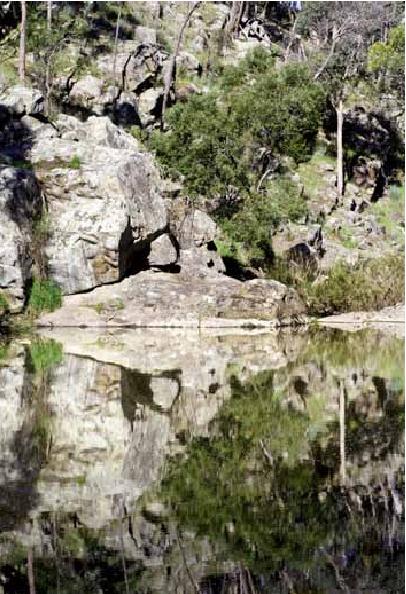

Reflections on the Loddon south of Vaughan Springs (Photo by Alison Pouliot)

In previous articles I've lamented the loss of human connection with the environment. This disconnection often stems from the tendency to view humans as separate from ‘nature'. Our current day approach to water, to water markets, to water trading, to water as a commodity, is a prime example of this rift. It seems, strangely, that many also view water as separate from the environment. Yet surely we're all fully aware that this is the same environment to which we're all inextricably linked. We tend to forget that that the economy is a mere overlay on the environment; that is, it's the environment underpins the economy, not the contrary. Yet economic interests inevitably take priority over environmental interests.

I don't pretend for a moment to understand the complexities of economics, but surely the ethics of applying economic principles to water is dubious. It's a commonly voiced argument that water trading promotes more efficient allocation as market-based price encourages users to allocate resources from low to high value activities, but the environmental and social impacts have been largely overlooked. Part of the problem stems from the belief that everything is quantifiable and can be slotted neatly into economic models. But can one put a figure value on the sense of well-being inspired by a chorus of croaking frogs, the joy of watching a heron take flight, or a fish population able to survive because it still has some water in which to swim? Critics may view this simply as green sentimentality, but is this not the stuff that keeps us sane and whole, ignites our imaginations, gives meaning to our existence and defines what it is to be human? Is it not simply about making wise decisions to protect the very surrounds that allow us to exist? Despite the spin of economists and politicians, not everything is measurable in this world.

It seems that water trading has been very cleverly marketed and supports the fallacy that water can be sold without environmental consequences. Yet many highly regarded scientists argue that water trading is neither environmentally nor economically viable. Such a scenario might work in a country with surplus supply. But that country isn't Australia. We still don't seem to fully appreciate the value of rainwater as a resource. Only under the pressures of drought did governments finally wake up to the benefit of installing household water tanks. Token water saving campaigns have done little to shift our position as the country with the highest per capita water-use in the world. Given that we live on the world's driest inhabited continent, surely it comes back to real human responsibility and conscious and efficient water use.

Common sense

The Loddon squeezes past lichen-covered boulders near Glenluce (Photo by Alison Pouliot)

While there may be many parallels between environmental and economic modelling, in regard to water trading, economic measures appear fundamentally incompatible with environmental principles. When environmental principles don't align with economic priorities, the environment essentially gets shafted. My intention isn't to reproach water policy makers, many of whom are highly regarded colleagues with genuine environmental concerns. Yet we should continue to question the propaganda of government schemes such as water trading and emissions trading that protects the dirtiest polluting industries by allowing them to ignore environmental standards by simply buying the ‘right to pollute'. It seems, sadly, that the more become embroiled we become in the water debate, the more we lose sight of good old common sense.

Returning to the Loddon, I hope that one day we will regard water, rivers, the Loddon, as something more than a mere utility. I believe that we are slowly developing a sense of stewardship and responsibility to reverse, where still possible, the past abuses of our river systems. To do so, we must first reconcile the ‘imagined division' between the natural environment and humanity.

We know that water is precious. Water in the Wombat that rolls into the Loddon is especially precious as it supports a swag of threatened species such as growling grass frogs and powerful owls. The Loddon catchment was once a supply of water, fish and other fauna for the Dja Dja Wurrung and other Aboriginal peoples. They inherently understood this environment and were inseparable from the land. From their connectedness, we can begin to understand their belonging and responsibility for the natural environment. And from this, we too can learn how to reconnect with the environment, with the Loddon River. The choice is ours. It's never too late to think differently.